Object-based visual search in cerebral visual impairment using a virtual reality and EEG paradigm

Abstract

Introduction: Cerebral visual impairment (CVI) is the most common cause of pediatric visual dysfunction in industrialized nations (Kong et al. 2012). Individuals with CVI frequently demonstrate difficulties with visual search, such as locating their favorite toy in a toy box. These impairments are particularly evident with increasing task demand and presence of distracting elements (Jan et al. 1987; Jan, Groenveld, and Anderson 1993). Successful object-based visual search requires intact networks of higher-order visual processing areas. Because the brain injury associated with CVI may impact the function of these regions, visuospatial performance and visual search is likely to be significantly impaired (Boot et al. 2010; Fazzi et al. 2004; Merabet et al. 2017). Yet, the neural correlates of impaired object-based visual search in this population remain unknown. In this direction, we combined eye tracking and EEG with a visual search task in which participants locate a target toy amongst distractor toys in a virtual reality (VR) toy box environment.

Methods: A total of 46 individuals participated in the behavioral study (CVI n = 11, mean age = 18.4 ± 3.9 years; controls n = 35, mean = 21.2 ± 4.5 years). A subset of 10 individuals equally split between CVI and controls completed the EEG study. Testing was carried out using desktop VR, a Tobii 4C eye-tracking unit, and a 20-channel Neuroelectrics EEG system (international 10-20 montage, solid-gel electrodes). The stimulus consisted of a 5×5 array of toys presented on a 27” monitor and participants were instructed to find and fixate on the target toy. For the behavioral study, 3 runs of 35 trials each were completed. Trials lasted 4 seconds and conditions were balanced across runs of low, medium, and high number of distractor toys (for additional details see (Bennett et al. 2018)). For the EEG study, the VR task was limited to the low and high levels of distractors. Epochs focused on the initial 1000 ms of stimulus onset with 500 ms pre-stimulus baseline. Post processing included average channel re-referencing, FIR filtering, ICA for removal of eye movements and non-physiological artifacts, and epoch rejection based on amplitude threshold as well as visual inspection for remaining artifacts.

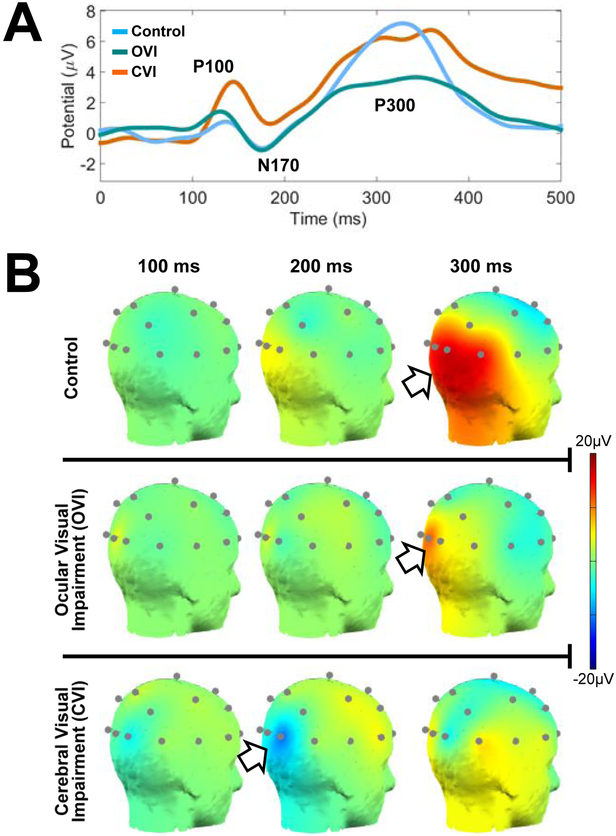

Results: Behavioral outcomes revealed significant differences between the CVI and control groups for gaze error (p<0.01) and reaction time (p<0.01), measures of the spread of gaze search data and time to fixate onto the target respectively. Furthermore, error and time for the CVI group fluctuated with varying levels of task complexity (not seen in the control group). EEG data revealed that individuals with CVI demonstrated marked differences at the n170 and p300 events and during the late positive potential (LPP) compared to controls. Specifically, CVI participants showed a reduction in magnitude of the n170 event as well as increased amplitudes of the p300 event and during the LPP. In addition, while the CVI group showed signal fluctuation in early visual processing regions as controls, signals in higher order visual processing areas (such as parietal cortex) were less robust and showed greater modulation with increased visual search demands.

Conclusions: These results indicate that individuals with CVI have greater difficulty performing object-based visual search tasks compared to controls, particularly in the presence of a high number of distractors. This was observed in our behavioral analysis and in the EEG signal fluctuations recorded from early and higher-order visual processing areas. Differences in EEG activity may represent a failure of proper selective inhibition, elevated levels of attentional effort, and fatigue during the visual search process. Overall, our behavioral and imaging results support previous observational reports of the visual deficits observed in individuals with CVI (Zihl and Dutton)